By Mihai Popsoi

After having visited Georgia several times since my first visit in 2016, I am in awe with the sheer splendor of the country’s booming new architectural landmarks. The controversial former president Mihail Saakashvili undeniably left a mark by embarking on a rapid modernization process that entailed drastic anti-corruption reforms as well as large investments in infrastructure. All over Georgia one can see the glass monuments to transparency, accountability and revival starting from the new offices of the Legislature, Presidency, Courts, Police Stations etc. One can discuss the aesthetics and the architectural value of the new edifices, but their symbolic importance for the young and ambitious country is unquestionable. Meanwhile, in stark contrast, Moldova has struggled for almost five years to renovate its parliament and failed to renovate the presidential office for almost a decade following the riots of April 2009. The Moldovan President Igor Dodon had to ask the Turkish President Erdogan not just to rebuild the Presidential Office, but also pay for the furniture.

Meanwhile, Georgia not only built dozens of large new public buildings, but also renovated hundreds of historical sites in Tbilisi, Batumi, Borjomi, Sighnaghi, Mtskheta etc. The government was also able to build hundreds of kilometers of highways, which, along with economic liberalization and good governance practices, further boosted the country’s business climate. Unlike Moldova, which employed opaque schemes to hand over management rights of the Chisinau International Airport to shady local oligarchs and sold the country’s national airline to equally obscure local business interests, Georgia invited reputable international investors into the Georgian Railway company, namely the U.K.-based Parkfield Investment. Similarly, Tbilisi Airport was sold and Batumi Airport was leased to the Turkey-based TAV Airports Holding, in turn owned by Aéroports de Paris. All these actions allowed Georgia to dramatically increase its revenue from tourisms. Perhaps nowhere is the transformation more vivid than in the small but famous town of Borjomi and even more so in the second largest Georgian city – Batumi.

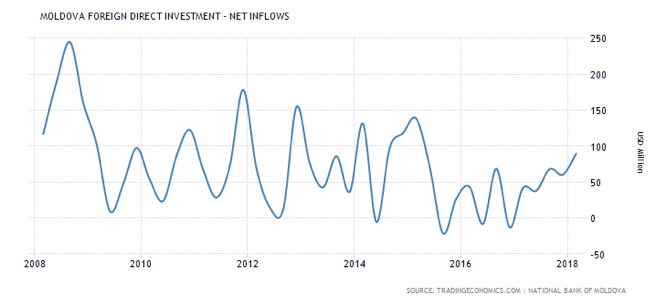

Following the ousting of Aslan Abashidze from Adjara in 2004, Saakashvili moved the Georgian Constitutional Court to Batumi to foster regional development as well as a spirit of national unity in the Autonomous Republic of Adjara. He was successful in ensuring the withdrawal of a Russian military base from the region, which bolstered investor confidence. The Batumi skyline now boasts impressive skyscrapers owned by Turkish, Azeri, Kazak and Russian investors. The town is home to world class hotels: Sheraton, Radisson Blu, Hilton, Wyndham, Golden Palace etc, while the entire Moldova only has a single premier hotel – Radisson Blu. This is indicative not just of the overall level of economic development, but could also be viewed as a proxy of the current state and future potential for foreign direct investment. One need only to compare the two graphs of FDI flows in Moldova and Georgia to get a rather stark contrast between the realities of the two countries. While Georgia reached almost $800 million in FDI around 2015 and had two lower peaks at about $600 million in 2008 and 2017, Moldova is still far away from its maximum of $250 million FDI achieved in 2008 during the rule of the Party of Communists.

Yet, the success of Batumi is important not just form an economic perspective, but also from a political and security viewpoint as well. Having regained full control over the region in 2004, the government in Tbilisi has been consciously investing in Adjara – the autonomous region and in Batumi in particular – the country’s second largest city. Again, in stark contrast, Moldovan leadership, including the more recent nominally pro-European elites, failed to see the value of consciously investing in the development and wellbeing of citizens living in Moldova’s own Autonomous Region of Gagauzia (in the south) and the country’s second largest city – Balti (in the north). As a result, the citizens living in those regions feel economically and politically excluded and remain heavily susceptible to pro-Russian agendas, further undermining the still very weak sense of national unity in Moldova. This perceived disenfranchisement is certainly not helping in terms of pulling Transnistria closer to Moldova proper. Elites in Chisinau have adopted the cliché of saying that Gagauzia needs to flourish in order for the autonomy proposition to become viable for Transnisnitria’s consideration within the conflict settlement process, but the same elites in Moldova have so far been reluctant to put their money where their mouth is, unlike the more visionary Georgian leadership.