Support for the European Union in Georgia is surprisingly high. When Georgia was granted a visa-free travel to the Schengen area, former British Ambassador to Georgia Alexandra Hall Hall wrote: “While this [visa-free travel] is a landmark achievement for Georgia, counterintuitively, in some respects it is a bigger deal for the EU.” The logic behind this statement is that against the background of Brexit, Georgia celebrating a “small step” on its path to Europeanization is a heartening sign that “the post-Cold War ideal of a Europe ‘whole, free, and at peace’” was still alive.

The Georgian government takes pride in the fact that over 70 percent of the population approves of joining the EU. However, what is often overlooked — or viewed with suspicion — is the opinion of ethnic minorities. There is a need to engage with ethnic minorities and inform them of what Europeanization of Georgia implies and what it means for them in practical terms.

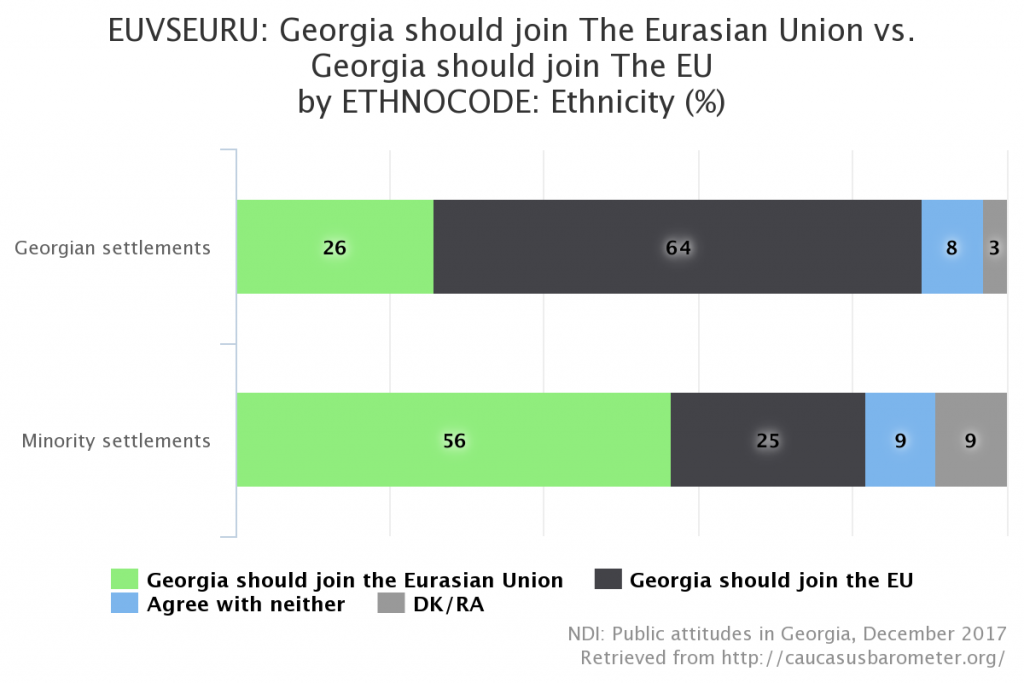

According to the latest polls, support for EU membership among minority settlements is 21 percent lower than the national average and stands at 51 percent. The proportion of undecided respondents among minorities is three times higher — 20 percent. Moreover, respondents from minority settlements are twice more likely than those from Georgian settlements to support joining the Eurasian Union as opposed to the EU (see chart 1).

“There is a need to engage with ethnic minorities and inform them of what Europeanization of Georgia implies and what it means for them in practical terms.”

While this is a problem for Georgia if it wants to achieve a national consensus over its Europeanization, this issue is in fact symptomatic of a deeper problem — Georgian minorities’ higher vulnerability to Russian propaganda in comparison to ethnic Georgians. Because low level of support for the EU among ethnic minorities is an effect and not a cause, it should not be viewed as the grounds for suspicion towards whole communities. Rather, this effect needs treatment, which is currently insufficient in Georgia.

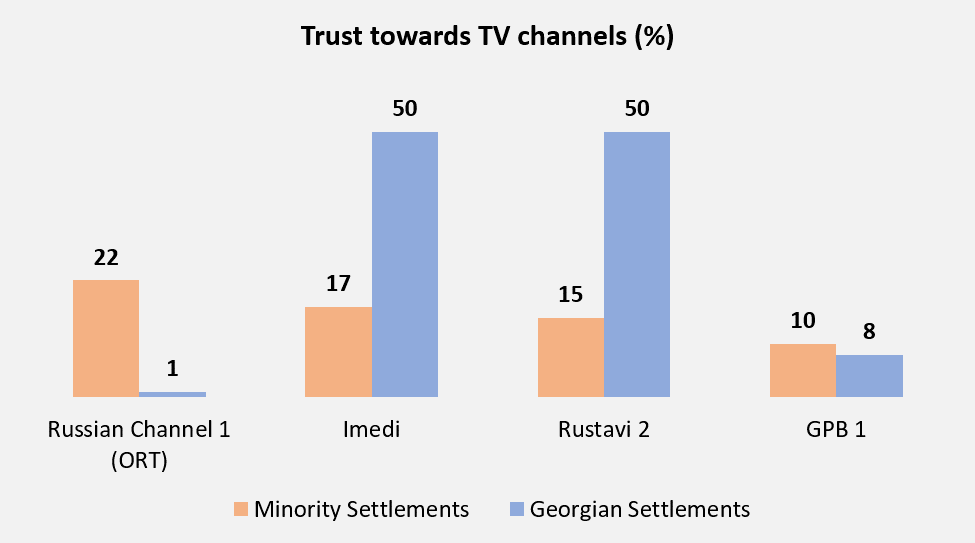

The issue is how ethnic minorities are typically informed about politics and how they perceive Russian propaganda. Primarily, the challenge is that ethnic minorities do not think that there is Russian propaganda in Georgia. Only 18 percent of minority respondents agreed there is Russian propaganda in Georgia, while the same figure for ethnic Georgians is three times higher at 57 percent. The second challenge is that 24 percent of minorities follow politics on Russian TV channels on a daily basis — and additional 9 percent do it at least once a week. Finally, the third challenge is that among all TV channels, Russian Channel 1 is the most trusted TV channel among respondents from minority settlements (see chart 2).

Even among those minorities who believe that Russian propaganda is present in Georgia, many believe that Georgian TV stations are more likely to be channeling Russian propaganda than non-Georgian TV stations – 36 percent and 27 percent respectively. Considering that television is the primary source of information for 59 percent of Georgian minorities, it becomes apparent how important it is that ethnic minorities in Georgia receive unbiased information that is free from propaganda.

These challenges are not easy to overcome, especially in the context of limited resources. However, the solution is not necessarily to replace Russian TV channels. The more important goal is to decrease the vulnerability of ethnic minorities towards Russian propaganda.

Consequently, it is important to engage with minority communities and ensure that they are not against Georgia’s Europeanization and in fact prefer the European Union over the Eurasian Union. However, there is a danger of raising expectations without delivering on promises. Not only is it important that ethnic minorities prioritize the EU over the Eurasian Union, but also that this should be achieved through constructive engagement from the government and civil society. Otherwise, raising expectations too high might create a different dilemma that will need remedies of its own.

Levan Kakhishvili is an EDSN Fellow and a Researcher at the Georgian Institute of Politics and the Center for Political Research at the International Black Sea University. As an Invited Lecturer, he also teaches at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University and International Black Sea University.